When seeking clues about the future effects of possible climate change, sometimes scientists look to the past. Now, a paleobiologist from the University of Missouri has found indications of a greater risk of parasitic infection due to climate change in ancient mollusk fossils. His study of clams from the Holocene Epoch (that began 11,700 years ago) indicates that current sea level rise may mimic the same conditions that led to an upsurge in parasitic trematodes, or flatworms, he found from that time. He cautions that an outbreak in human infections from a related group of parasitic worms could occur and advises that communities use the information to prepare for possible human health risks.

Trematodes are internal parasites that affect mollusks and other invertebrates inhabiting estuarine environments, which are the coastal bodies of brackish water that connect rivers and the open sea. John Huntley, assistant professor of geological sciences in the College of Arts and Science at MU, studied prehistoric clam shells collected from the Pearl River Delta in China for clues about how the clams were affected by changes caused from global warming and the resulting surge in parasites.

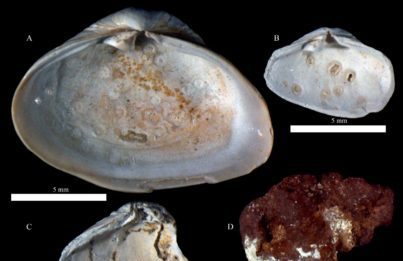

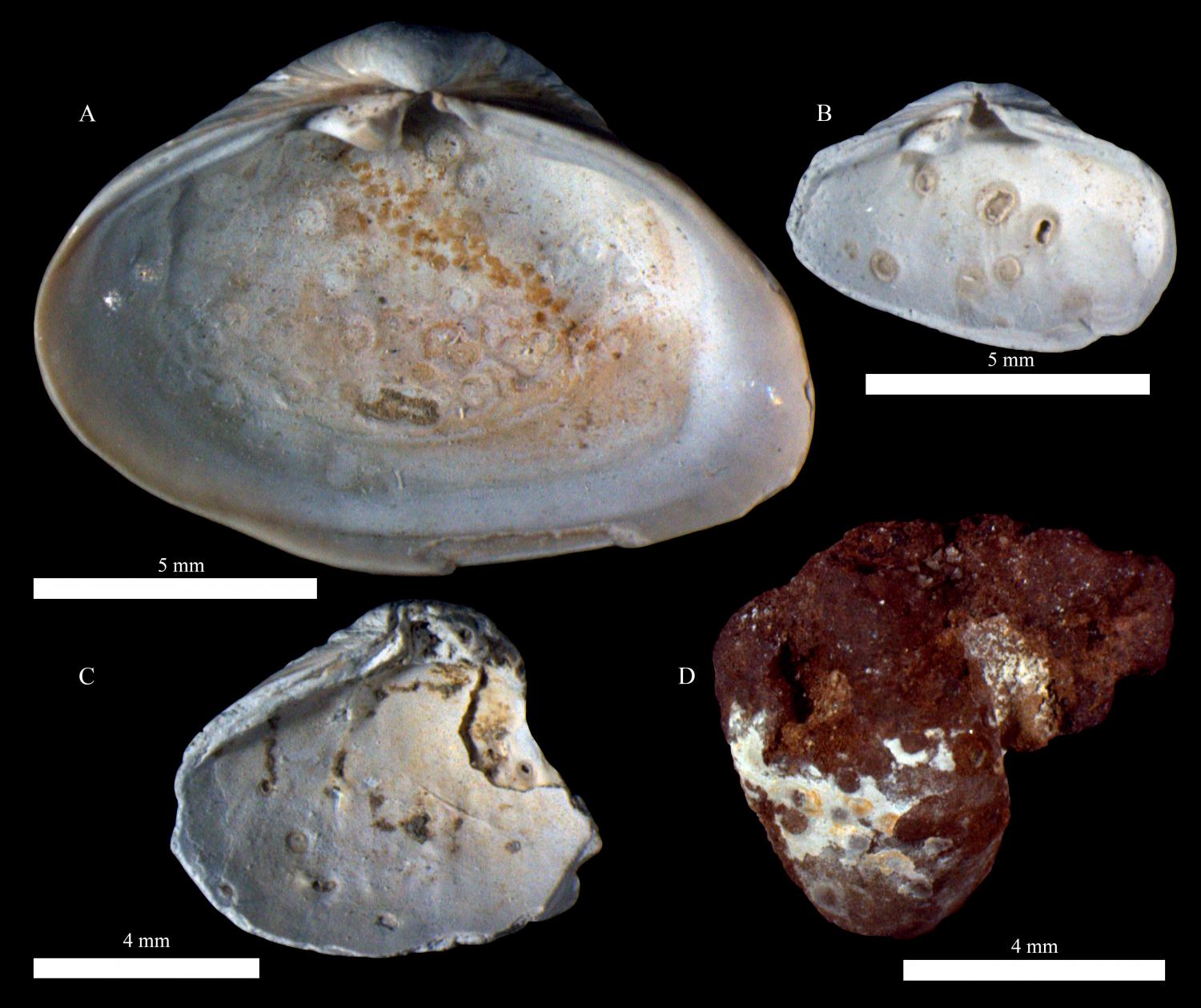

Huntley and his team compared these findings to those from his previous study on clams found in the Adriatic Sea. Using data that includes highly detailed descriptions of climate change and radiocarbon dating Huntley noticed a rising prevalence of pits in the clam shells, indicating a higher prevalence of the parasites during times of sea level rise in both the fossils from China and Italy.

“By comparing the results we have from the Adriatic and our new study in China, we’re able to determine that it perhaps might not be a coincidence, but rather a general phenomenon,” Huntley said. “While predicting the future is a difficult game, we think we can use the correspondence between the parasitic prevalence and past climate change to give us a good road map for the changes we need to make.”

The study, “A complete Holocene record of trematode-bivalve infection and implications for the response of parasitism to climate change,” was funded in part by the University of Missouri Research Council, the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and the National Foundation of China (Grants 40872024 and 40272011) and recently was published in the journal, The Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.