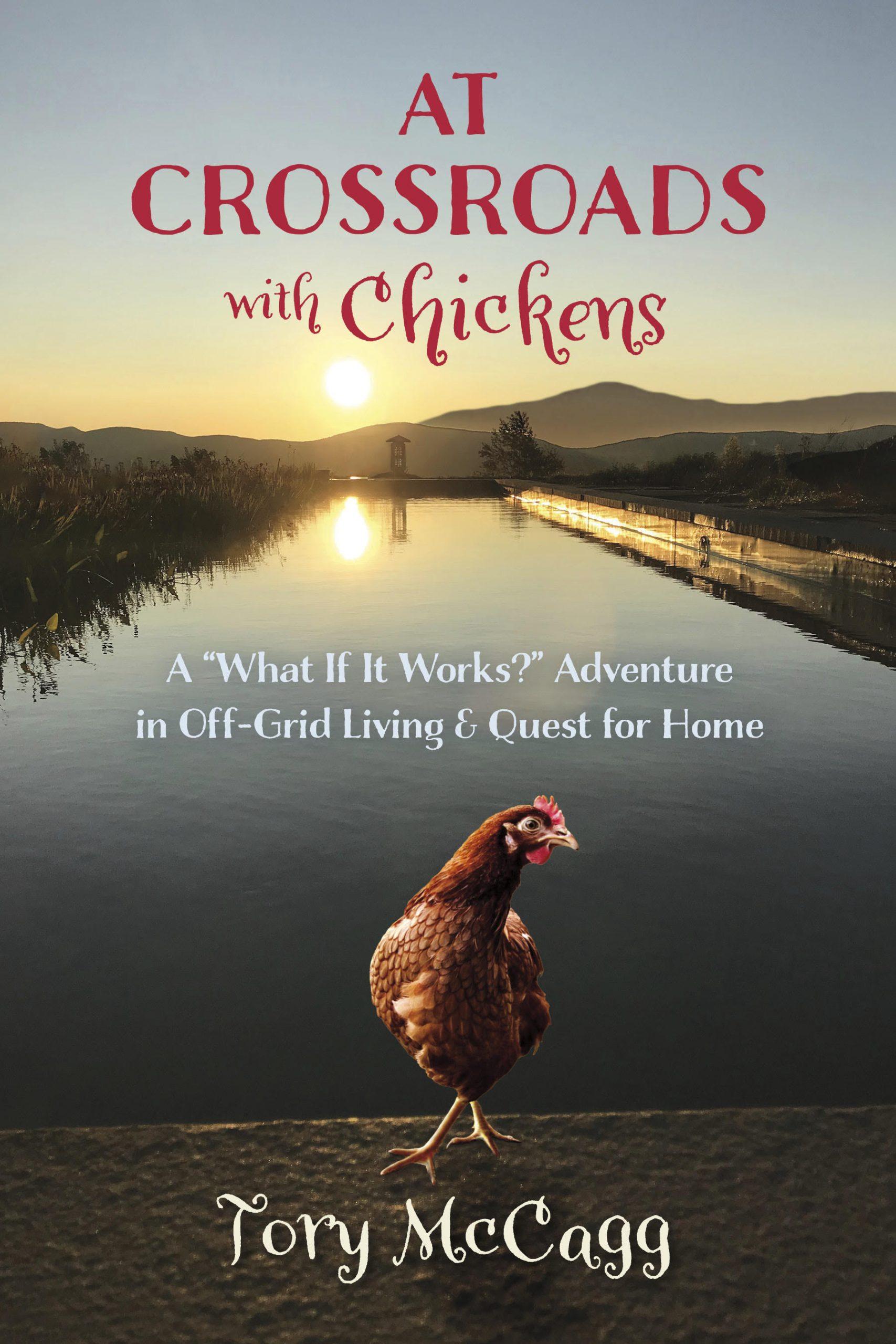

In 2012, Tory McCagg and her husband, Carl built an off-grid, solar-powered house in Jaffrey, New Hampshire. It was to be a weekend getaway for the writer (“what’s this pitchfork for?”) and trombonist (a wannabe farmer). In December, with two cats and six newly adopted chicks, they drove up to Jaffrey from their home in Providence, Rhode Island, ostensibly just for the winter so their new pipes wouldn’t freeze. . . . But their hen “Rhoda Red” turned out to be “Big Red.” Roosters are outlawed by Providence city regulations, so Big Red couldn’t go back. Thus, writes McCagg, “neither did we. Survival of the fittest. Natural selection. Soul evolution. We named our 193-acre home “Darwin’s View” for a reason.” Chicken kerfuffles lighten the mood, but this story is born of heartbreak, of yearning for the great beauty of the world as it used to be. As she moves from full-time weekender to organic gardener, McCagg’s interlaces her tale with her mother’s battle with Parkinson’s, braiding both Mother and Mother Nature. Add the sun, the wind, and a cock-a-doodle-do, and you have the recipe for a perfect storm of personal growth rippling out to effect a larger transformation.

Enjoy this excerpt from the book;

Our generator-upon which we depended on sunless days because we have no wires to connect us to anything beyond our little hill-went straight-up splat against my image of off-grid. To me, off-grid meant fossil-fuel free. Propane gas brought to my mind images of once pristine lands raped of their flora and fauna, blackened by tar, and cluttered with pipelines, ravages of nature as heinous to me as vegetarianism is to some beef-eating Americans. That image was one of the reasons we moved off- grid. We didn’t want to be part of that system.

Eh, voila! Once again, my hypocrisy rose like a phoenix. Carl and I might have appeared to have lowered our carbon footprint by being off- grid, we might have deluded ourselves into thinking we were taking our- selves out of the fossil-fueled system, but an analysis of our externalities proved that, despite all our efforts, Carl and I epitomized our society’s lack of sustainability and love of convenience. We maintained two houses, one of which might have been off-grid, but what of the devastation wrought by its building process? Hundreds of trees timbered. Soils uprooted, deep- ly disturbed, and, in places, eroding. Solar panels that are made of rare and precious metals, and we couldn’t ignore the gasoline used to get us be- tween our two houses, to gigs, to the grocery store, and to other points of interest. Who was fooling whom? The only real difference between us and an on-grid house was that, when there were blackouts or power outages elsewhere, our lights still shone.

Usually.

Few trees had escaped the 2006–2007 timbering of our hilltop. Those that remained were debilitated by the ice storm of 2008. Of those that sur- vived, we had some removed to provide full sun exposure for the solar panels. Thus, there wasn’t so much as a blade of grass to stop the volumi- nous breezes coming over Mount Monadnock from slamming against the house and battering the chickens’ Hay Chalet. Every night, three to five times a night, I would wake, my body tensed against the seemingly mortal danger of the winds that hammered the house. They convinced me that we were fools to be there.

Early on in our just-for-the-winter venture, while attempting dinner conversation over the outside din, I commented that the house sounded remarkably like an old, wooden boat, one of those Spanish Armada galle- ons creaking and moaning in the middle of a typhoon.

“We aren’t going to sink,” Carl reassured me.

“Obviously,” I said. “But the house might get blown down.” “Nothing is going to take out this house.”

“That’s what they said about the Titanic,” I remarked, just as the French doors that faced Mount Monadnock bowed in under the force of the most recent west wind blast and we heard a loud pop.

“Just the house timbers settling in,” Carl said as we both sat back down in our chairs and another gust hit the house. I found it a pyrrhic victory that Carl finally looked nervous.

Not that he admitted it. A very New Hampshire trait, to be uncon- vinced by weather.

“Ah, yuh,” you’ll hear when you comment on the blizzard conditions, the ice, the negative wind shear. “That’s what you might expect, it being wintah.” And so at dinner parties, when guests comment on the wind, the doors bowing, the good fortune of an overbuilt house that could never be taken

out by mere cyclones, I have learned to say, “Ah, yuh. We’ve had worse.” At which point people ask why we don’t have windmills.

“The wind’s dirty,” we reply in unison. Coming over the mountain and

swooping down and up, the wind is blustery and uneven. It might do to a very expensive windmill what it did to our anemometer the first day we put it up. Carl and I had sipped our morning elixir of Santo Domingo espresso roast cafe lattes, and watched, rapt, the anemometer’s receptor screen. It showed the wind averaging thirty to forty miles an hour, forty-five, and then a gust slammed against the house. The screen flat-lined. Very bad tim- ing. No anemometer and Blizzard Nemo tracking its way toward us.

That first winter at Darwin’s View, the winter of 2012–13, had more Biggest Storm Of The Century! alerts than had ever occurred in the brief history of humankind and the Weather Channel. Somewhere in our coun- try, someone was getting slammed. More often than not, it was us. Having spent years worrying about the world’s lack of snow due to the warming climate, it felt reassuring to be in the thick of it again.

The beauty of snow? You can see the wind that is so eminently present at Darwin’s View. Shrieking ghosts. Pale viragos chasing scampering, dia- pered cherubs across the fields. Whirlwinds bashing against tumbleweeds that suddenly calm to nothing, only to rise up as fields of whistling grasses, oceans of frost. Whorls of energy that left parts of our hilltop (the chicken coop) six feet deep in snow and parts (the cars) swept free. And still the wind. Still the snow. On top of a hill. Off-grid. With solar panels, not windmills.

Winter days are short, the result being less sun. And though daylight might come, when it’s snowing, there is even less less-sun. Like none. If you depend on solar panels for your electricity and there’s no sun, the batteries that would usually run the electricity in the house run down. Fortunately, we had our propane generator backup system. Every third or fourth day of no sun, the roar of the generator, typically starting up just as I turned on the espresso machine, assured us that all was in working order. Until, one day, it didn’t. Not that we noticed, because the batteries still worked. It’s just they weren’t supposed to get used down to the very last drop. It’s not good for them.

One of the questions we were asked by our off-grid energy consultants in the planning stages was this: When you arrive at your off-grid house, do you want to flick a switch and have the lights turn on, or are you okay with having to check how the system is working? My response: flick a switch. Carl’s: How does it work?

Carl’s and my yin/yang approach: whereas I prefer to spend my time on the whys of life, he asks the hows, which is far more helpful and rel- evant when in the middle of a blizzard and the generator is not working, a fact that Carl finally noticed when he went to check the batteries in the basement and noted that the inverter had gone into default. Thus, while I remained inside, worrying that Carl would get lost in the woods to our north, to be found in the spring inside the trunk of a dead tree where he had sought protection, Carl opted to take some initiative and a posteriori test the wind velocity by troubleshooting the generator’s untimely somnolence.

I didn’t mean to compare. Comparing is unhealthy. It causes resent- ment and anger. But there we were, two months into our little experi- ment, all by ourselves on our lovely hill with all kinds of amusements, like wind, snow, and ice, and I had the stark realization that I preferred city living. Where we didn’t have to stoke a wood-burning stove five times a night. Where we didn’t have to drive for fifteen minutes to arrive somewhere, anywhere. Where the walk to a market is not eight miles and past a shooting range and, thus, where a black- and brown-toned city wardrobe doesn’t have to be replaced with florescent orange. Most important of all, though, in a city, I could delude myself into thinking I could take care of myself. I could pretend, as does every good American, independence from things I am entirely dependent on.

But in the country, I am surrounded by acres of land we were supposed to be stewarding and living with a man who thrives on being outdoors in frigid cold, proof being his conviction that skiing in a blizzard is the penultimate form of fun. In the country, there is too much to learn and know, none of which includes sitting down in a cozy chair and reading a book. Thus, the dis-ease I had felt that first time Carl brought me to New Hampshire had not changed. Au contraire.

And so I compared. For just a moment, staring out into the darkening skies, deserted by Carl, who had already either died of a turbo-charged electric shock from the generator or disappeared into a Darwinian Ber- muda Triangle, thereby leaving me to fend for myself, I compared and felt resentful. I had given up too much in this move to New Hampshire. I was unprepared. It wasn’t fair!

And then the roar of an engine and my resentment melted into grati- tude. Thank goodness for our Subaru. Carl was warming it up to drive me back to Rhode Island, right? No.

Bought in 1998, the Subaru was a tank and a truck all in one and, by 2013, in its dotage. One symptom: It would lock, then unlock its doors. Lock, unlock. Lock, unlock, lock, unlock, lock unlock. At the same time, its lights blinked. Blink-blink. On, off, on, off, onoffonoff. All this while the engine was off. Thus, the battery would die. Time and again, and this time, too. When Carl stepped off the porch to go to the generator, the Subaru, perhaps out of joy, like a lovesick puppy, began to lockunlocklockunlock and blinkblinkblink, then died. I would have left it to sit. There was a bliz- zard going on, after all. Carl, ever the hands-on guy and fully energized by the weather, jump-started it (thus the roar of the engine of the car, not the generator) and left it to run while he dug the generator out of the snow. At which point, he realized the Subaru (lockunlocklock) had locked him out.

While he attempted to jimmy the lock, ice forming on his long eye- brows, I braved the elements to shovel the girls out of the Hay Chalet for the third time that day. Upon arriving at the door, I dipped into the run. Hay bale walls blocked the wind, leaving me to wonder if we shouldn’t have used the same for our house. Also, the hay that served as the floor had begun the composting process. My unwitting success at deep-litter mulching made for radiant-heated floors. The hens cooed and clucked. The atmosphere was gentle and soothing. Reassuring in their visceral calm, the chickens were being. No worries. Their only concern: Where were the treats? At which point, a peck, a squawk, and feathers flying. Big Red chas- tised and directed until the hens settled back down around him and me, too.

Kneeling down in the run, I listened to the hens rustling and studied their social etiquette. Panda and Lola groomed themselves on either side of Big Red. CooLots uh-ohed off in a corner. Ping and Chipper, side by side, caballed. Death felt very far away. The only suggestion of necrosis was Big Red’s comb, which was blackened by frostbite. For all the time I had spent googling possible remedies, the fault pointed back to the human element, drafts, and moisture. Big Red looked at me with disapproval. What good was I if I couldn’t heal his comb?

Bowed, I crawled back out of the coop and faced the buffeting, shrill winds of Blizzard Nemo. The ice cold reddened my nose and pinched my cheeks. Struggling to maintain my footing against the wind, I watched the snow sweep across the fields. It was a stunningly beautiful winter after- noon and my self expanded in the maelstrom, alive. Noting the car’s head- lights in the darkening skies, the running engine, I stomped the snow off my feet and headed inside. Carl hovered by the stove, warming his hands. In the dark. I reached to flick a switch.

“Don’t do that,” he said. “The generator isn’t turning on.”

“Excuse me?” I asked. Though I knew. Off-grid. No sun. No generator? But I am the one who, from day one, said I wanted those light switches to work because I live in the twenty-first century. Ever with my priorities in order, I asked, “Will we be able to use the espresso machine tomorrow morning?”

Carl called the generator guy, who, in the course of his interrogation of us, asked why we hadn’t built a box around the generator to prevent it from sucking snow into itself, thereby freezing the system. And was the propane gas tank shoveled out? It needed air, too.

Now then, who would have thunk to build a box around either of those objects? Not us, in part because the generator company that installed the generator had said nothing about building a box around a generator that already has a metal box around it, one bought specifically for its added protection. Putting a ventilated box over a ventilated box? That’s like having a piece of equipment that tests wind velocity burn out on the first slightly windy day it’s up and running.

Thus, we had no anemometer for the two worst snowstorms in history.

Thus, we had frozen our generator, and the emergency generator com- pany’s on-call guy didn’t have four-wheel drive.

If one were to be judgmental, one might ask why an emergency gener- ator company based in New Hampshire doesn’t provide its employees with some semblance of four-wheel drive transport. But we were not ones to judge. At least, we tried not to, so full of faults ourselves. Besides, this was an adventure! We were adapting! Evolving!

That weekend, we did no laundry, nor did we vacuum. We allowed ourselves one latte per day and didn’t charge our computers or cell phones. We had candlelit dinners with no technology to distract us. We couldn’t remember the last time we’d had a candlelight dinner.

Ever the “how it works” guy, and using a solar flashlight, Carl went down to the basement to see how many watts we were using: 150. The refrigerator was the only thing electric running in the house. We had only candlelight and the light from the wood-burning stove to see by. It was very quiet. Still. Because this was life off-grid in the twenty-first century. All the luxuries of a regular house, when the sun shines.

Award-winning writer Tory McCagg is the author of multiple short stories, a novel, and the memoir At Crossroads With Chickens: A “What If It Works? Adventure in Off-Grid Living And Quest For Home. An accomplished flutist, McCagg lives with her trombonist husband, one cat and myriad chickens at Darwin’s View in Jaffrey, New Hampshire where they all practice an experimental life off-grid and on the land.

Reprinted with permission of Bauhan Publishing, Peterborough, New Hampshire. All rights reserved.