Racism is a public health crisis,” according to a 2020 statement from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). This means that racism – whether unintentional, unconsciously, or concealed – has affected Black Americans’ access to equal and “culturally competent” health care.

For example, it has been widely reported that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black Americans. According to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, the death rate for Black Americans nationwide is 2.5 times higher than the rate for white Americans: 67 per 100,000 vs. 26 per 100,000.

Employees of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent a letter to their director alleging “widespread acts of racism and discrimination within CDC that are, in fact, undermining the agency’s core mission” that may have indirectly contributed to that disparity.

Just as some medical facilities have been overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases, increased anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – in people who are worried they might catch the virus or have been impacted by the lockdown and social isolation needed to control the pandemic – may, in turn, overwhelm the mental health system.

Racism is also a stressor for mental health problems.

How Racism Causes Mental Health Problems

In the U.S. surgeon general’s groundbreaking 2016 report Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, it states that Black Americans “are over-represented in populations that are particularly at risk for mental illness.”

Why? NAMI, “the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization,” says it’s because Black people in the United States have been affected by racism and racial trauma “repeatedly throughout history.”

That is, racism and racial trauma did not end with the abolition of slavery in 1865, the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the election of the first Black U.S. president in 2008. The protests in 2020 are a sharp reminder of that.

Mental illnesses such as depression and substance abuse can have a biological component, but they also can be caused or made more likely by external factors. Some are more likely to be experienced by Black individuals, including:

- Violence

- Incarceration

- Involvement in the foster care system

Some other factors are peculiar to the Black Americans’ history, such as:

- Enslavement

- Oppression

- Colonialism

- Racism

- Segregation

Encounters with Police

“Black Lives Matter” is viewed as a controversial statement, but it shouldn’t be. It does not mean that only Black lives matter or that other lives don’t matter. It means that Black lives also matter.

The controversy comes from the implication that the speaker thinks, based on the evidence, that not everyone agrees with that sentiment.

Take fatal police shootings. Analysis published by the Washington Post found that, in 2019, 55 unarmed individuals died due to police interaction. Of those, 25 or 45% were white, while 14 or 25% were Black. The rate for Black people remains about the same when extended to all 1,002 deaths: 250 or 25%.

However, Black people represented only 13.4% of the American population in 2019 (approximately 44 million) – almost one-sixth of the white population’s 76.3% (250 million) – according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

When only males are counted, the rate is even higher, according to a University of Michigan study, with Black men and youths 2.5 times as likely to die as white males.

On the other hand, that might be explained by the number of crimes committed by Black people. Black Americans were more likely to commit violent crimes than white Americans – 52% to 45%. More violent, crime, more violent interaction with the police.

Black people also face higher rates of nonlethal encounters with the police. An analysis of 2015 data by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found that while police stopped white people more often than Black people, they were more likely to stop a higher percentage of Black people based on their population, including:

- 9.8% vs. 8.6%: traffic stops – driver

- 2.5% vs. 2.3%: traffic stops – passenger

- 1.5% vs. 0.9%: street stops

- 0.5% vs. 0.3%: arrests

Such police stops, and sometimes multiple stops, may create feelings of ill will towards the police, but the damage can be even more severe for mental well-being.

Feeling oppressed – by law enforcement, by employers, by politicians, by realtors – can lead to physical and mental health problems regardless of whether it is objectively true or is accepted by society at large.

Common Serious Mental Illnesses Among Black People

Among Black Americans with any mental illness, 22.4% or 1.1 million had a serious mental illness (SMI), according to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): African Americans.

According to the the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health (HHSOMH), Black Americans are 20% more likely to experience serious mental illness (SMI) than the general population.

But other sources claim the rate of SMI is the same or even less for Black people. This seems odd, since poverty influences some SMIs, and Black Americans are more likely to experience poverty.

These results might be skewed, however, due to “culturally oblivious measurements.” There may be a communication barrier even among fellow English speakers from different cultures.

Depression

For example, experts say Black Americans sometimes talk about their depression in terms of physical aches and pains. If health care providers are not culturally competent about this form of expression, they might not realize this.

More than just the blues, depression is a serious mental illness and mood disorder characterized by extreme sadness and emptiness, a feeling that nothing matters or is worth doing.

Depression can increase the severity and risk of both physical and mental illnesses, according to the 2009 book Say It Loud! I’m Black and I’m Depressed, and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) agrees. “The risk of developing some physical illnesses is higher in people with depression,” and people with a medical illness or condition are more likely to have depression.

Among these risks are:

- Cancers of the prostate, colon, and lungs

- Heart disease or stroke

- Liver disease

- Osteoporosis

- Diabetes

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Poor self-esteem

- Drug abuse

- Infectious diseases such as hepatitis B or C and HIV/AIDS

Types of depressive disorders include:

- Major depressive disorder. Also known as clinical depression, this is depression that lasts for at least two weeks.

- Persistent depressive disorder. Depression that lasts for at least two years.

- Peripartum (or postpartum) depression. Depression lasting more than two weeks following the birth of a child.

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). A particularly debilitating form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) causing deep depression.

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Depression brought on by the waning hours of daylight in the fall and winter.

- Bipolar disorder. Formerly known as manic depression, this is depression that alternates with periods of mania or exuberance.

- Psychotic depression. Depression accompanied by delusions and hallucinations of a depressive nature.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is normal and even helpful. One definition is “a heightened state of readiness” that alerts to and prepares for potential threats.

A diagnosis of anxiety disorder means the individual worries about things far more than is warranted. The worries are so intense that they interfere with the individual’s life and ability to function.

There are many types of anxiety disorders, including:

- Panic disorder. A sudden fear, as if one is going to die, accompanied by physical symptoms that may resemble a heart attack.

- Phobias. A fear of some specific thing or situation, such as open or crowded spaces (agoraphobia), heights (acrophobia), or confined spaces (claustrophobia).

- Separation anxiety disorder. Fear of separation from someone to whom one is close.

- Social anxiety disorder. Fear of being judged or shunned by others.

- Generalized anxiety disorder. When many things cause excessive or uncontrollable worry.

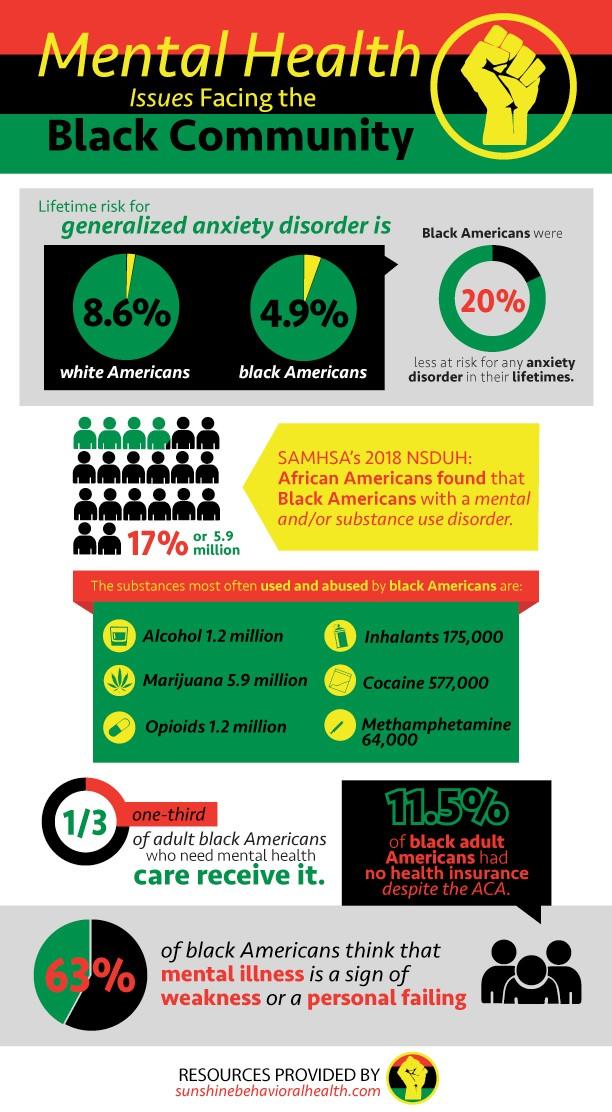

According to one study, the lifetime risk for generalized anxiety disorder is 8.6% for white Americans compared to just 4.9% of Black Americans. Another study concluded that Black Americans were 20% less at risk for any anxiety disorder in their lifetimes.

Suicide

Suicide is the act of causing one’s own death deliberately. While it is not a mental illness, it may occur because of mental illness.

For example, depression seems to increase the risk of suicide. As many as 60% of people who commit suicide had depression or bipolar disorder. Also, 7% of men and 1% of women with a lifelong history of depression eventually commit suicide.

Not that one has to be mentally ill to commit suicide. The goal of suicide is not death but to end suffering. Persecution, such as caused by racism, may be enough on its own.

According to the University of Michigan, suicide is the second most common cause of death among young Black men after accidental death (such as from drug overdose and motor vehicle traffic).

Younger persons who kill themselves often have a substance abuse disorder in addition to being depressed.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Trauma is most commonly associated with returning soldiers experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but besides combat, many things can cause trauma, including:

- Being in or seeing an automobile accident

- Rape

- Domestic abuse

- Violent crime

Watching the video of George Floyd with a police officer’s knee on his neck may also cause trauma or PTSD. So might the fear of experiencing a similar incident one’s self if stopped by the police.

While trauma causes biological or physiological changes to the individual, those changes may be passed along to future generations not just culturally or psychologically but genetically, through the DNA, just like physical characteristics.

This could help explain why changing laws and extending rights, creating a so-called level playing field, doesn’t solve the problem by itself.

Experiencing trauma can also cause ongoing problems with relationships and self-esteem.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, Black youth who are exposed to violence are more than 25% more likely to have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse or substance use disorder (SUD) is a form of mental illness and a physically dependent disease. Both mental illness and SUD are covered under the same “essential health benefits” provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

SUD is not a sign of weakness of character or a lack of morals. Some people are genetically predisposed to addiction. In those people, substance use is more likely to rewire the brain, hijacking the reward center, causing continued and increasing substance use.

In the 2018 NSDUH: African Americans, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that 5.9 million or 17.8% of Black Americans had a mental disorder and/or substance use disorder.

The substances most often used and abused by Black Americans are:

- Marijuana: 5.9 million

- Alcohol: 1.2 million

- Opioids: 1.2 million (including prescription fentanyl, hydrocodone/Vicodin/Norco, oxycodone/OxyContin/Percocet, and heroin)

- Cocaine: 577,000

- Hallucinogens: 474,000

- Inhalants: 175,000

- Methamphetamine (meth): 64,000

Substance use disorder and mental illness often co-occur, one causing or exacerbating the other. When this happens, it’s known as a dual diagnosis, comorbidity, or simply a co-occurring disorder.

Among Black Americans with a substance use disorder (SUD), more than two-thirds (67.6%) abuse alcohol, almost half (47.1%) abuse illicit drugs, and almost one-seventh (14.8%) abuse both.

Why Don’t More Black People Seek Mental Health Help?

According to the U.S. Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, Black Americans are less likely to have their mental health problems addressed than Americans as a whole: about 30% compared to 43%.

While most studies find about the same or less (depending on age) incidence of mental health problems among Black Americans, they are less likely to seek help for it. Only one-third of adult Black Americans who need mental health care receive it.

Reasons include:

- Systemic racism. One psychotherapist calls it “post-traumatic slave syndrome” (PTSS). Because slaves weren’t considered human, it was thought they couldn’t experience mental illness. Because of PTSS, descendants who have not directly experienced such discrimination may still feel the effects.

- Financial considerations. In 2018, one analysis found that 11.5% of Black adult Americans had no health insurance despite the Affordable Care Act. That makes affording mental health services difficult.

- Faith-based alternatives. In parts of the Black community, the church is more trusted than physicians and maybe with good cause. Black Americans who are members of a church or similar organization do have a lower suicide risk. Unfortunately, priests and ministers aren’t trained to treat or recognize mental illnesses by themselves. Professional help may still be needed.

Stigma

A big barrier might be that there is still a stigma or shame attached to needing mental health treatment, especially among the Black community, because people may believe that:

- Mental illness is a sign of weakness or a personal failing. According to one study, 63% of Black Americans think that. Faith communities, despite their good points, can perpetuate or reinforce this attitude.

- It might reflect poorly on their families. Many people still think the therapist’s go-to is to blame problems on their clients’ mothers and fathers.

- Talking to a therapist is airing dirty laundry in public. Such problems should be addressed by the family or larger community, not strangers. Except they often don’t.

Removing this stigma – or at least disregarding it – is necessary to get more Black Americans into treatment that can improve their lives.

Among the ways to do this are:

- Teaching people that the brain is like any other part of the body: sometimes it needs to be examined by a physician.

- Replacing the idea that mental illness is a weakness with the idea that it takes strength to acknowledge a problem and to try to fix it.

- Explaining how taking prescribed medication isn’t like drug abuse. Sometimes medications can restore normalcy in conjunction with therapies.

The Importance of Culturally Competent Care

One major way to remove stigma and racial barriers is to have more Black and culturally diverse physicians and psychotherapists. Not to meet affirmative action quotas, but because their existence improves trust and care.

A Black surgeon is more aware of and sensitive to concerns that a white surgeon might not be. A 2018 study by Stanford University found that Black men had much better medical results when their doctor was also Black.

There still is misinformation about Black bodies out there: that their skin is thicker or that they aren’t as sensitive to pain. A common background can dispel such faulty knowledge.

For example, a Black woman in North Carolina chose a Black cosmetic surgeon to remove some benign bone growths on her skull because he seemed more concerned about her and her wishes to minimize scarring and hair loss.

Due to his familiarity with natural Black hair, he also braided her locs (hair) for easy postoperative care. It was a small thing, but it improved the woman’s surgical experience.

Even when it’s not a matter of life or death, simple cultural sensitivity can help.

Finding Culturally Competent Mental Health Providers

Significant health care hurdles may include the lack of sufficient numbers of Black mental health care professionals, scientific studies specifically of Black people, and treatments tailored to their needs and preferences. Without such culturally competent care, misdiagnoses are more likely.

Unfortunately, a 2018 survey by the Association of American Medical Colleges found that of active doctors in the United States, only 5% identified as Black, as opposed to 56% who identified as white.

And the Association of Black Psychologists’ Therapist Resource Directory has no listings in 19 states (though that doesn’t mean there are no Black psychologists there).

If Black American clients can’t find a Black American doctor, they can look for one who is culturally competent. Ask them if they have treated other Black Americans or received cultural competence training for treating Black Americans. Then, ask yourself if they listened to and understood your concerns and treated you with dignity and respect.

Black Mental Health Resources

Here are some free or low-cost sources for mental health treatment of the Black community:

- AAKOMA Project. Arlington, Virginia-based but serving the Northern Virginia and Washington D.C. area, offering up to three free virtual mental health sessions for “young people.”

- Black Men Heal. Limited and selective (no guarantees) free mental health service opportunities following a waiting period.

- Ethel’s Club. Brooklyn-based group offering live-streamed weekday classes, workshops, and wellness sessions for the Black community. The first week is free, up to three sessions a day. Also, free virtual healing and grieving sessions as available (there’s a waiting list).

- Boris Lawrence Henson Foundation. To help Black Americans with “life-changing stressors and anxiety” receive mental health services, the organization’s Free Virtual Therapy Support Campaign pays for up to five individual sessions – first come, first served – “until all funds are committed or exhausted.”

- Henry Health. Culturally sensitive self-care support and teletherapy for Black men and their families. “The first out-of-pocket session is on us.”

- Inclusive Therapists. With a directory of therapists offering reduced-fee teletherapy.

- Family Paths. “Mental health and supportive services to low-income, multi-stressed individuals and families” in Alameda County, Calif.

- The Loveland Foundation. Financial assistance is sometimes available for between four and eight sessions for Black women and girls.

- National Queer and Trans Therapists of Color Network. A directory of mental health practitioners working in agencies, community-based clinics, and private practice. Also, a mental health fund that provides financial assistance to queer and trans people of color by queer and trans people of color.

- Open Path Collective. A nonprofit that for a one-time membership fee provides inexpensive in-network therapy, online and in-person.

- Talkspace. Live video psychiatry sessions, plus a free therapist-led racial trauma support group, and financial assistance for the Black community.

- Therapy for Black Men. Free therapy sessions for Black men are in the planning stages. You can sign up to be notifications when they become available.

- Zencare. Provides a list of Black therapists – primarily in Boston, New York City, and Rhode Island – some of whom “offer a sliding scale, lower fees, or out-of-network reimbursement for individuals who cannot otherwise afford to pay for therapy.”

Here are some sources for culturally competent mental health providers:

- Association of Black Psychologists Directory.

- Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective (BEAM).

- Black Female Therapists.

- Black Male Therapists Directory. Provided by Black Female Therapists.

- Black Men Speak.

- Black Mental Wellness. Apps, podcasts, videos.

- Black Virtual Therapist Network. Provided by the Black Mental Health Alliance.

- Brother, You’re on My Mind. Provides educational materials on mental health issues affecting black men, particularly Omega Psi Phi Fraternity members, with an online toolkit.

- InnoPsych. Resources to find a therapist of color.

- LGBTQ Psychotherapists of Color Directory.

- Melanin and Mental Health. Directory of “Dope Therapists.”

- My Tru Circle.

- Ourselves Black. Directory of providers, plus a podcast, online magazine, and online discussion groups.

- Sista Afya Community Mental Wellness. Chicago-area organization providing sliding-scale rates for mental health treatment for Black women.

- Therapy for Black Girls. “An online space dedicated to encouraging the mental wellness of Black women and girls,” with a therapist locator, in-office and virtual, plus a blog, podcast, and online community.

- Therapy for Queer People of Color. Therapist directory.

Sources

- nami.org – NAMI’s Statement on Recent Racist Incidents and Mental Health Resources for African Americans

- pbs.org – How the stress of racism can harm your health-and what that has to do with Covid-19

- npr.org – What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State by State?

- npr.org – CDC Employees Call Out Agency’s ‘Toxic Culture of Racial Aggressions’

- rollcall.com – Virus forebodes a mental health crisis

- nami.org – Who We Are

- columbiapsychiatry.org – Addressing Mental Health in the Black Community

- washingtonpost.com– Giuliani Falsely Claims That Black People Kill More Police Than Vice Versa

- cnn.com – Black communities account for disproportionate number of COVID-19 deaths in the US, study finds

- news.umich.edu – Police: Sixth-leading cause of death for young Black men

- channel4.com – Do black Americans commit more crime?

- bostonglobe.com – The statistical paradox of police killings

- bjs.gov – Contacts Between Police and the Public, 2015

- nami.org – Black/African American

- mayoclinic.org – Mood disorders

- books.google.com – Say It Loud! I’m Black and I’m Depressed

- nimh.nih.gov – Chronic Illness & Mental Health

- webmd.com – Types of Depression

- mentalhealth.org– Living with Anxiety

- columbiadoctors.org – Anxiety Disorders

- webmd.com– Anxiety Disorders

- vice.com – Is Anxiety a White-People Thing?

- hhs.gov– Does depression increase the risk for suicide?

- pnas.org – Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race-ethnicity, and sex

- mcleanhospital.org – Trauma and Dissociative Disorders Treatment

- huffpost.com– This Is What Racial Trauma Does to the Body And Brain

- dartmouth.edu – Dual Diagnosis: Mental Illness and Substance Abuse

- samhsa.gov – 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: African Americans

- webmd.com – African Americans Face Unique Mental Health Risks

- webmd.com – Types of Mental Illness

- instyle.com – 10 Free and Low-Cost Therapy Resources for Black People and People of Color

- samhsa.gov – 2018 NSDUH Detailed Tables

- health.state.mn.us – Legacy of Trauma: Context of the African American Existence

- mcleanhospital.org – How Can We Break Mental Health Barriers in Communities of Color?

- kff.org – Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity Since the ACA, 2010-2018

- usatoday.com – ‘We’re losing our kids’: Black youth suicide rate rising far faster than for whites; coronavirus, police violence deepen trauma

- mhanational.org – Depression in Black Americans

- abpsi.org – The Association of Black Psychologists – Therapist Resource Directory

- yahoo.com – Woman who woke up from surgery with hair braided by doctor makes the case for more Black physicians: ‘It can save lives’

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov– Mental Health Care for African Americans (Chapter 3: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General)

Stephen Bitsoli, a former magazine and newspaper journalist in Michigan, is a content writer and editor for Sunshine Behavioral Health.